Is ageing the result of sin, or part of God’s good creation? In this two-part article, ISCAST Publications Director Dr David Hooker explores the scientific, biblical, and pastoral perspectives of getting old.

This article was originally published in a two-part series in the 2021 September and October issues of The Melbourne Anglican.

PART 1

On sheer numbers alone, we face a tsunami of older people. In 2018 and for the first time in recorded human history, people over 65 outnumbered those aged under five, with the United Nations predicting that by 2050 the over-65s will be more than double the number of under-fives. Globally, people over 80 are the fastest growing of any population fraction. In the words of one commentator: “Age no longer has the value of rarity. In America, in 1790, people aged 65 or older constituted less than 2% of the population; today, they are 14%. In Germany, Italy, and Japan, they exceed 20%. China is now the first country on earth with more than 100 million elderly people.”

Just like the ocean wave that catches people unprepared, it would seem that the world is not ready for this tsunami; we are ill-prepared on attitudinal, emotional and ethical levels. The ancient Greek veneration of the young and aversion toward the elderly is an early and influential example of a long history of negativity toward the aged in Western society that continues today. Old age is perhaps the only life-stage that often evokes responses of fear, disgust and even hatred. These responses include the fear of decline, morbidity and impending mortality, disgust by the non-aged over the unpleasantness of bodily decline, and hatred in the form of elder abuse, which, according to the World Health Organisation, is a widespread and growing global problem. “Ageing anxiety” is prevalent in those experiencing the onset of decline and, for those still young, ageism, the discriminatory stereotyping of the aged, keeps getting old at arm’s length. On this, theologian and ethicist Frits de Lange explains: “Ageism may function as an anxiety buffer, keeping the awareness of ageing and its inevitable decline and ending at a distance, by constructing a cultural worldview of growing older, in which everything that reminds us of deep old age at the threshold of death is kept far away.” Meanwhile, some scientists are working on “trans-humanist” possibilities of stopping the ageing process and even reversing it, acting as if ageing is a defect or disease that needs to be conquered. Overall, it seems that we struggle to accept and assimilate the aged and the ageing process.

As Christians, what theological resources do we have to respond intelligently and with love to the realities of this tsunami of the aged? Unfortunately, a Christian understanding of ageing is beset with inconsistencies, omissions and controversies.

First, there is the question of whether human ageing is an aspect of God’s good creation or a result of sin. On this, the giants of Christian theology disagree. For example, the great Reformation theologian John Calvin says ageing is “among the blessings we receive from God”. Yet he appears to contradict himself when he also says: “It is on account of our sins that we grow old and lose our strength.” Other theological giants—such as Augustine, Aquinas and Wolfhart Pannenberg—argue that ageing is a result of sin. Moreover, numerous biblical interpreters argue that when humanity fell into sin, the creation degenerated in a way that includes ageing.

In contrast, Karl Barth, perhaps the 20th century’s most eminent theologian, arrives at a thoroughly positive perspective on the ageing process. And Augustine, despite his negative perspective outlined above, promotes the concept of a currently good creation with the implication for ageing being that it, too, forms part of a good creation. Thus, from some of the greatest Christian thinkers we discover an obvious and indeed troubling lack of consistency.

Another question is whether Christian theology is engaging specifically enough with the question of ageing. The answer is that while Christian thinkers have much to say on creation, sin, death and the image of God in humanity, they say comparatively little on ageing, which is a matter so intimately related to all those themes. Even prominent theologians tend to apply basic theological affirmations to the phenomenon of ageing without developing a focused theology of ageing. As one commentator says: “There is no special theology for the ageing. There is only the one biblically and confessionally based theology which is applied to the problem of older adults.”

A third question is that of our openness to learn from the science of ageing. On this, theology has been left behind by rapid scientific progress into both the ageing process and also the transhumanist possibility of extending life indefinitely. Again, only a minor proportion of theologians offer a compelling voice. One such distinguished thinker is Pannenberg, yet even his appreciation for the natural sciences does not incorporate the most current understanding of the ageing process. More recently, the prominent theological ethicist Gilbert Meilaender asks the question, “Should we live forever?”, in his book of that name. He considers the place and power of science to extend life indefinitely. However, he chooses not to focus on the scientific question “How do we age?” in favour of the question of God’s purpose for ageing, “Why do we age?”. This leaves a gap in theology’s engagement with the science of ageing. In his book, This Mortal Flesh, Christian social ethicist Brent Waters investigates medicine’s drive for human transformation and also follows Meilaender’s track, likewise not engaging with the detailed mechanisms of ageing that are coming to light in the 21st Century.

Another question for theology is that of how to relate our ageing to that pivotal entity in Christian faith and understanding: death. It is here that we hit a puzzling challenge, especially when we do allow contemporary science to partner with Christian theology. Consider the following: popular Christian understanding and indeed much of Western theology forges a strong link between humanity’s fall and human physical death. We commonly assume that sin leads to physical death. Yet medical science tells us that the ageing process leads to death. So, it appears that ageing is the mechanism that enacts the fall’s effects. However, what if ageing was shown to be the result of genetically determined processes? Theologically, would such processes be understood as the manifestation of the fall or of the good creation? And if we conclude “of creation”, what implications does this have for ageing and natural physical death in the doctrines of Christian theology?

A final question, more practical than theological perhaps, is about decline—that increasing limitation or loss in body and mind that comes with ageing, often with the accumulation of maladies and infirmities. Perhaps the most challenging question of all is how can we assimilate and accept decline and loss into our Christian understanding of life?

How can we assimilate and accept decline and loss into our Christian understanding of life?

The way we answer these questions will have a profound effect on how we view “getting old” and our attitude to the older people around us. As Christians, we are called to offer an intelligent, compassionate and unified voice to the world, but on the matter of getting old, we are not. In the second part of this article, we will look at possible answers to these questions, especially whether ageing can be understood as good in the biblical creation sense.

PART 2

Is human ageing really part of God’s good creation? In Part 1 of “Getting old: What shall Christians think?” we read of a troubling lack of consistency among great Christian thinkers. Some see the ageing process as being due to sin’s entrance into this world; others claim a thoroughly positive outlook on ageing that sees it as a blessing from God put into creation.

In this second part, I suggest that ageing indeed is a part of God’s good creation. Let’s look at the science first. What has helped the understanding of ageing enormously in the last 30 years is the science of molecular biology. Understanding what molecular biology is all about is a bit like understanding what goes on in a high-tech factory at Toyota or Ford or Holden. There are assembly lines, carefully controlled processes, specialised equipment, intricate mechanisms that make, cut, join, and mould things, and it’s all coordinated by the head office. That’s similar to what goes on in a cell. Molecular biology can find out what those cell processes and mechanisms are, what controls there are, what’s made or unmade at the cell’s assembly lines. Where’s the head office? We may think of our genes as the staff in the head office, tasked with coordinating the many mechanisms of the cell. But, as we know, the human body is far more complicated than one cell; it’s made of groups of cells, organs and systems, all of which are coordinated and work together beautifully like a mega-factory.

So where does ageing belong in this picture?

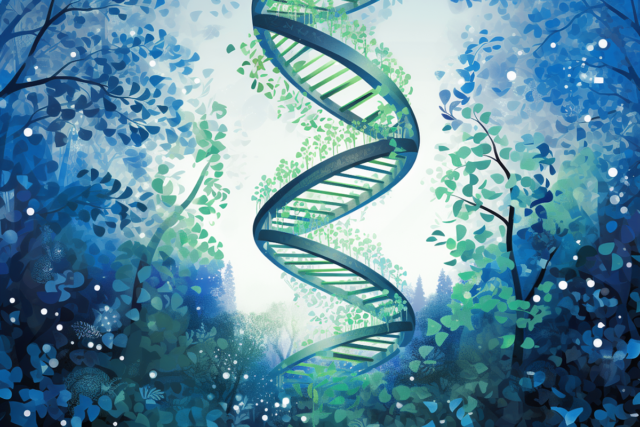

One of the strongest theories of ageing, backed up by thousands of publications, is to do with telomeres – the ends of human chromosomes. As we live and grow and our cells divide, the ends of chromosomes become steadily shorter until the cell receives signals within itself to shut itself down. Once this happens, the cell may die or simply stop working. Either way, over time more and more cells reach this stage, then groups of cells start to decline, and organs decline, until the whole human body winds down, in a sense. This is ageing.

Does this sound like a kind of “mistake”? A kind of “fault”? After all, why should the chromosome ends get shorter? Yes, it does sound like a fault. Until we appreciate an amazing discovery – the location where the commands for chromosome shortening originate. They come from the head office of our cells – the cells’ genes. In other words, it’s a part of our genetic code, part of who we are as human beings. Of his own body, King David praises God in saying: “You made all the delicate, inner parts of my body and knit me together in my mother’s womb … Your workmanship is marvellous!” (Ps 139:13, 14 [NLT]).

There is much more to the story of how ageing happens. Does the brain have a role in ageing and in determining lifespan? Here, scientists are searching for answers beyond the events in a cell; they want to find out whether, and how, the body as a whole system might cause ageing. The focus has been on the brain’s hypothalamus – a truly remarkable control centre for life and health. Among its many roles, it controls reproduction and sexual development in males and females, our use of energy, and regulates body temperature and our wake-sleep cycle. It is truly a master regulator, one that deserves a healthy degree of awe and wonder.

But much more recently, scientists have uncovered a new role for the hypothalamus. As well as all its roles in life and health, it actually programs the end of our reproductive years and regulates the ageing process. As the authors of this work write: “Ageing is a life event that is programmed by the hypothalamus.”

If human ageing is of God’s original creation, then ageing is of God and it must be ‘good’ in the biblical sense.

This scientific work challenges how we think about ageing: we so often think of ageing as the antithesis of life and health and growth; yet, the very centre for so many life, health and growth events – the hypothalamus – is also a control centre for ageing. Life, health, growth – and ageing – seem to be built together into our bodies. This surprising idea is only strengthened when we realise that the indivisibility of life and ageing occurs not only at this higher level of an organ, but even within each cell: there are molecules and pathways and special parts in cells which are required for both life and ageing; without them we wouldn’t have a human body.

All of this challenges us to change our minds about ageing. It challenges us to move away from seeing ageing as a fault, as a penalty for our transgressions, as even a disease, or as something to be corrected. If human ageing is of God’s original creation, then ageing is of God and it must be “good” in the biblical sense.

And it may change our attitudes too. If we are young, have we felt an aversion against the aged? If we are getting old, are we anxious or afraid of it? Understanding the creational quality of ageing will help us form a new perspective, one that reaches out to God in faith and hope to accept ageing into our lives.

But our search for whether ageing is creationally good needs to go further. So far, we have only addressed the science of ageing. How about the book we hold so dearly, our Bibles? What does the word of God say? Abraham and Sarah’s childlessness (Gen 17), Isaac’s failing eyesight (Gen 27:1), Eli’s frailty (1 Sam 4), King David’s chills (1 Kgs 1), and Zechariah and Elizabeth’s advanced age that sealed their childlessness (Luke 1) are all transparent examples of ageing’s limitations and losses. So our Bibles are frank about ageing’s decline. Importantly, however, the decline of ageing does not diminish the aged person at all; quite the opposite: Israel is commanded to “revere the elderly”, a command paired with another command that gives it unique gravity: “You shall fear your God.” Even if we deliberately ignore the aged, pretending we hadn’t noticed them, the God who is to be feared has seen it. The limitations of ageing invoke a special relationship of grace and oversight from God. The Bible confronts us with the expectation that human care of those with limitations will reflect the carer’s devotion to God Himself (Lev 19:14,32; Deut 27:18).

Yet, our Bibles go further than admit ageing’s decline. Ageing actually adds to life and living: ageing builds humility by making us aware of our finitude (Isaac; Gen 27) and our sin (Jn 7:53 to 8:11), it is not considered a hindrance to a faithful and blameless life (God’s call to the elderly Abraham; Gen 17), nor to a life in God’s service (Anna; Luke 2). The aged receive a calling to pass on righteousness and wisdom to the young (Prov 16:31 to 17:7; Ps 71:18; Tit 2:2, 3); and they are a true part of community, as much as the young (Prov 20:29; Jer 31:1-14; Joel 2:28).

But does the Bible give any clues about whether ageing is really of God’s good creation? Yes – more than clues. From the Psalms and the prophets some remarkable insights are found. Psalm 148 recounts Genesis 1’s creation account and uniquely calls on all in the whole created universe to sing praises of God – not for their redemption but for their creation. The stars, planets and angels – the heavenly choir – are answered by the earthly choir: ocean creatures, mountains, trees, storms and animals, and “young men and maidens, old men and children” (verse 12). These are all creation categories, including the “old men.” This makes ageing a divinely recognised part of created life. And, from the prophets, images of Paradise and end-time salvation include images of the old, even frail, human being (Is 65:17-25; Zech 8:4). God‘s salvation does not “delete” ageing and the aged as if these are defective categories; rather, God’s salvation places the aged in blessed, peaceful and safe community.

God’s salvation places the aged in blessed, peaceful and safe community.

From the Bible, then, we find a positive, life-affirming picture of ageing. Ageing is a creation category that builds character, service and faith.

We may still wonder, however, how to truly accept ageing’s decline into our Christian understanding of life. Where is the “goodness” in everyday life for the very aged, the frail? Here, the communion of God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit has valuable lessons. In reflecting the Trinity, human beings only fulfil their true humanity as community, and this means dependence and interdependence. Both the aged and the community reciprocate in giving and receiving. A small true story from this author may help here:

On Christmas day some years ago my father and mother invited a very old spinster over for lunch. I was a young man at the time, and Dad asked if I could go with him to pick her up. I remember her now – in her 90s, thin, frail, hunched, walking slowly and awkwardly with a stick. Her tiny face was like a shrivelled prune – all long creases. She was blind. As we arrived home, she needed our side-by-side support to walk the long driveway, up the three steps to the back porch, along and up two more steps to be finally in the house. As she got there, she said “Oh! What a blessing!” without the slightest cynicism. We guided her to a lounge chair and there she sat down. I remember her face as she chatted and smiled. There was a happiness and peace that radiated the grace of God. Her name was Aunt Marion, and she was my sister-in-Christ.

Aunt Marion received our care. What did we receive as we cared for Aunt Marion? It is indeed more blessed to give than to receive. And we were blessed. In her frailty and loss Aunt Marion was weak, but her presence was strong and made an unforgettable impact on my life. I remember admiring her in her weakness. I felt a wonderment at seeing her joy in the midst of frailty. I was humbled by the combination of weakness and grace; this made me see the grumblings and cheap pursuits of my young life as needing change. This combination of weakness and grace adds power to a human life; they are integrated together as God’s plan for human life on earth.

Space has not permitted how two substantial challenges to the suggestion that ageing is creationally good may be addressed; one being the concept that humanity’s Fall brought ageing, the other being natural death as the consequence of the Fall.

We have endeavoured to show from science, from the Bible and from a more pastoral perspective how ageing could be creationally “good”. To allow our own ageing and the ageing of those around us to be part of God’s good plan for creation will serve to build a strong foundation for embracing life and giving glory to God in our older years.