Alan Gijsbers

May 2017

Download review (210 KB)

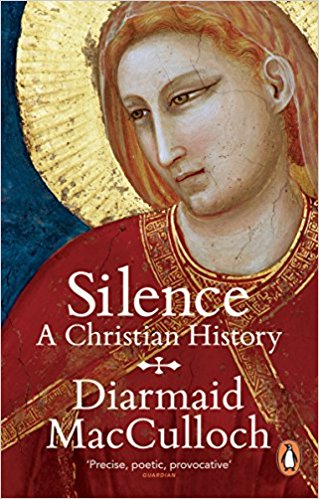

Book Review—Silence: A Christian Theology by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Viking, 2013. 338pp.

Alan Gijsbers is an Honorary Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, Royal Melbourne Hospital, University of Melbourne. He is a physician in Addiction Medicine and Head of the Addiction Medicine Service at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. He is President of ISCAST.

Why should ISCAST be interested in a book on the theology of silence, written by an historian, who asks how he, as an historian, uses silence as a clue to unravelling the history of events, while at the same time recognises that Christians have used silence in all sorts of ways in both public and private worship?

ISCASTians should be interested, first, because it is based on the 2006 Gifford Lectures. The Gifford Lectures were set up as annual lectures in Scotland over 100 years ago to “promote and diffuse the study of Natural Theology in the widest sense of the term—in other words, the knowledge of God.” ISCASTians have a special interest in the Natural Theology of the Gifford Lectures. In fact our most recent ISCAST Fellow, Peter Harrison, gave the 2011 Gifford Lectures.

Secondly, MacCulloch’s book is of special interest to scientists, who subscribe to the “two books” school of thought—the book of Scripture and the book of nature—the dialogue between which books ISCAST promotes. MacCulloch creatively explores an alternative dialogue between divine revelation by silence and human responses of silence. These prove to be minor but important dimensions of understanding divine revelation and act as a counterpoint to the over-wordiness of much Protestant thought and worship.

Thirdly, MacCulloch’s book is of special interest to me because it embraces such a wide range of Christian history, especially in the Eastern branches of the Christian church—traditions of which I, as a Western Protestant, was only dimly aware. I learnt a lot.

Finally, for me the book brings hermeneutics (the science of interpretation, especially of narrative) into sharp focus. As a clinician, I spend my time taking and interpreting histories from patients. My questions direct the narrative they tell. I listen not only to what patients say but also to the way they say it. I am also alert, or try to be, to what they leave out. Hence, I too interpret silences. Indeed, my silences can communicate thought and empathy; silences also speak.

As an historian, MacCulloch wants to uncover what really went on. Silence, he maintains, can be an important clue. While admitting that arguments from silence are notoriously ambiguous, MacCulloch is emboldened by Sherlock Holmes’ observation of the dog, who did not bark. (This provided an important clue as to who stole Silver Blaze, the racehorse!) Further, truth can be particularly distorted by those in power, and the Western Church, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, with its strong hierarchy and centralisation of power, has been very good at silencing dissent and marginalising those who disagree with it. The official story then becomes a very sanitised version of what actually took place. Even historians of their own lives can change their story with time, if they become ashamed of previous positions. Thus, Robert Boyle of chemistry fame tried to hide his past interest in alchemy and astrology.

There are many different silences, only some explored by MacCulloch. In the first half of the book he explores the role of silence in Scripture and Church history. Here he explores the silences of private devotion that attempt to enter the world of the divine, the numinous, the other, which so occupied introspective contemplatives to the exclusion of the outside world. He also explores silences in liturgy and the different ways that different branches of the Christian church, East and West, have oscillated between wordy and silent approaches to public worship. This leads to a discussion of the silent monastic orders, which ironically have developed a set of hand signals in order to communicate so that they can live together in a silent order!

As I read through MacCulloch’s review of worship, meditation, and contemplation, both individual and corporate, the story of Jesus and the woman at the well continually came to mind. Access to the Father is so simple, so universal—in spirit and truth, through the Son—so why does the church throughout the ages make it so complicated, either overwhelming it with excessive words or with artificial silences?

Histories reveal as much about the historian as the history they are telling. MacCulloch writes memorably. Telling the story of George Fox—the founder of Quakerism with its balance of silence, contemplation, and social activism, MacCulloch describes Fox as “endowed with the prophet’s enviable gift of supreme lack of doubt.” Fox denounces Puritan preaching: “Give over your railing and baulking, and backbiting in the Pulpits all people, for that is not to preach the Word of God.” Railing at Puritan wordy self-righteousness is an intriguing strand in MacCulloch’s story.

In the third section of his book, MacCulloch uses Calvin’s term, Nicodemism, to discuss a whole range of believers, who had to maintain some degree of silence to survive the different attitudes of those Christians in authority. Calvin coined the term (from the comfort of his exile in Geneva!), describing Christians in challenging places, who were wary of openly declaring their commitment to their brand of faith. MacCulloch, like the New Testament, is more sympathetic of Nicodemites than Calvin. It is an interesting history of the silence of Jewish, Islamic, and Christian dissenters in the face of “magisterial Christianity.” MacCulloch uses this term for the denomination which seeks to enhance its own standing by the exercise of political power, just as Calvin himself did in condemning heretical Servetus to death. From his broad view of the history of the church, MacCulloch identifies a wide range of Nicodemites.

In some areas, he overstates his case. For instance he dismisses the New Testament on three grounds, its anti-Semitic stance, its embrace of slavery and its poor treatment of homosexuality.

I can understand the shame he rightly feels over the Christian treatment of Jews, especially in the Holocaust. He is ashamed of the Church’s silence in the face of the way the Jews were exterminated, and he lays some responsibility on the New Testament’s description of the death of Jesus. However, I find his one-line dismissal of Jewish responsibility for Christ’s death an oversimplification, and I find it particularly surprising coming from an historian used to analysing complex causation. Yes, Jesus was crucified, and therefore it was a Roman execution, but one would have to rewrite the gospel narratives extensively to take out the lengthy feud between the scribes, Pharisees, and rulers of the Jews on the one hand and Jesus of Nazareth on the other. It is a feud from early on in Jesus’ ministry, which Jesus sometimes instigates and often inflames. It is a battle between a highly systematised and controlled religion on the one hand (magisterial religion?) and a godly prophet unfettered by religion on the other. It was a feud which led to Jesus’ death, instigated by these rulers and carried out by the Romans manipulated by these rulers. However, this is not a reason to become anti-Semitic, and it certainly does not justify the Holocaust. Jesus is quite clear on the need to forgive enemies. As Lesslie Newbigin in his commentary on John’s Gospel wisely points out, any religious system, including Christianity, can carry within it that same deadly approach to the dissenter and her truth. Maybe Jesus was not Nicodemite enough to save his own life—or else he was committed to a higher cause than just saving his own skin!

MacCulloch’s description of the fundamentalist justification of slavery is quite chilling. However, I am not sure that the New Testament justifies slavery quite as much as MacCulloch makes out. Maybe I have been affected by my egalitarian upbringing, but in my opinion Paul in his letter to Philemon implies that Onesimus, as a brother in Christ, is much more than Philemon’s slave. However, on careful reading, Paul does not unequivocally advocate Onesimus’ manumission. On balance, MacCulloch’s dismissal of the New Testament seems thus a bit cavalier.

MacCulloch discusses his own homosexuality: the love that dare not speak its name. At the beginning of his book, he describes his own experience of being gay and how that has contributed to his understanding of silence. When discussing the Nicodemites, he identifies homosexuality’s hidden presence in a number of Christian communities, especially within the Tractarian movement of the 19th century, although his attempt to “out” John Henry Newman seems unfair on the poor cardinal. He also identifies Geoffrey Clayton, Archbishop of Cape Town, as struggling with his sexuality to the extent that he had no energy left to battle apartheid. MacCulloch chillingly describes the existence of paedophilia within an Italian order of the 17th century, but his silence on the current paedophile scene is surprising, especially as he makes so much of the significance of silence. Was the Anglo-Catholic gay community really so innocent that it did not seek to exploit vulnerable young men and recruit them as victims into their paedophile rings? Not all gay attraction is exploitative but MacCulloch’s criticism of clerical celibacy leads to the logical conclusion that gays also need not be celibate. These are ongoing debates which the New Testament does not really address, except in its major ethical theme of the struggle between flesh and spirit, where flesh is a lot more than sexuality and its many and varied attractions and expressions. At least Clayton acknowledged the struggle!

Between silence and open discussion lies a whole spectrum of discretion and proper circumspection. On the silence side, there is effective listening. Here we are not just silent, but open to new ideas and new ways of seeing. We do not learn by talking but by listening. What constitutes the radical listening which hears truly? How do we see truly rather than blindly? And silence is not just dumb silence. Even MacCulloch is discreet in his description of some of the foibles of his fellow Christians. Tent-making missionaries and citizens in occupied countries behave circumspectly.

Does silence speak? Jewish Rabbi Chaim Potok in his novel The Chosen explores the Hasidic tradition of using silence in the bringing up of children. Danny’s father brings the brilliant young Danny up in silence so that he will become tender of soul and personally resourceful. It deepens Danny, but the novel is ambivalent about the value of raising children in silence. In the sequel, The Promise, Danny, now a trainee psychologist, uses silence to break down young Michael’s ego defences therapeutically. While the novel speaks sympathetically of such an approach, it has not become a mainstream counselling strategy.

There are thus other dimensions to silence than those covered by MacCulloch, who, however, casts a lot of light on this dimension of Christian thought. MacCulloch’s book is a very stimulating read, provoking both thought and emotion. It is a book worth engaging with in order to develop a better understanding of different Christianities: it forces us to recognise the degree of interpretation that we use in the stances we take. So, he provokes us to understand better current issues and to confront our own complicit silences in seeking to be righteous, just and merciful in our lives together.